This review is not going to contain spoilers but it is going to talk about the book in detail so if you wanted to read it and feel like this would spoil it for you, then here is your warning to stop reading and go and get the book!

Also, there are brief mentions of sexual assault in this post. If this is something that you are uncomfortable with or unable to cope with, I won't blame you for skipping it. Take care of yourself.

*

I've started this year very motivated. To do what, I'm not sure, but I'm very full of energy. I want to write. I want to watch as much cinema as I can get access to. And most pertinent to this post, I want to read as much as I can. I managed to complete my Goodreads challenge of 2020 of reading 50 books, the second year in a row I've done this, despite constantly believing throughout the year, that "I'm not reading enough". Who am I even comparing myself to at this point? 50 is a lot of books.

I've set the same goal this year as well, with the added caveat that I'm not buying any more new books for myself. I have so many books on my shelf that I have either never read or I have read but I've never given them a rating on Goodreads. I'm going to make a dent in my ever-growing pile. I hope.

|

| Source: Drawn & Quarterly |

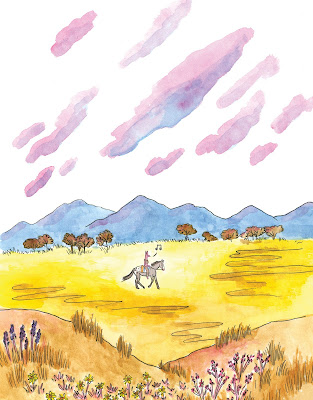

I started this year off strong, beginning with a graphic novel I've been wanting to read for a long time, Coyote Doggirl, written by Lisa Hanawalt. To give a brief synopsis, this book follows a half-dog half coyote woman as she escapes her previous life by venturing out into the wild with her horse, Red. I would say more than that but it would difficult. Both because I feel like I'd spoil the book, but also because though the story is linear, it is also quite sparse on plot, focusing on being a character study. We are following Coyote as she experiences a new space, where her adventures are there to provide character development rather than be the focus of the story.

Lisa Hanawalt has made of career of anthropomorphising animals, forcing us to see the animality in ourselves and see the humanity in animals. Coyote Doggirl invites us to view the Western in its truest sense, too wild for a human woman and instead only available to a woman who is half-coyote and half-dog. And even with this, she is in danger at all times. Even in the quiet moments, she is being hunted out of vengeance and these moments become only brief respite. The reader is made aware that this character will have to face what is coming after her. Her being not human gives her the opportunity to react in a less tentative way, taking the path that will solve her problem and also put her in the most danger.

This book shows the reader a harsh truth - if a woman wants independence, she must also be prepared for backlash, for being put in immediate danger. Coyote owns her house and business, and she is made to flee both of these. When she enters the wild, she is consistently in danger, from the various people hunting her and from the underlying dangers of the landscape itself: dehydration, starvation, being eaten or killed by other animals. Even with all of this, this book fully asserts that choosing the wild, choosing independence is the correct choice. Along with this, it doesn't assert that this character should fully reject community. She spends much of the novel with a native tribe where she integrates for a short time and is able to heal from her wounds. The balance between needing a space to be independent whilst being able to be a part of safe place, where you are sheltered from gendered violence is an escapist fantasy that Hanawalt seems to capture.

The Western landscape as shown in most media is consistently unsafe. There hasn't been a moment in which moving from a civilised space to an uncivilised space is free from danger, to the extent that people venture out into it for the sake of facing said danger in order to defend their civilised space. Whilst this book depicts this, we are taken through this space outside of the masculinised point of view that we are used to. The danger that the protagonist faces is that of sexual assault, of gender-based violence. Her home becomes unsafe, so she risks going out into the wild as a result. In this, she does find danger, but she also finds community and companionship.

Hanawalt is able to appropriate and transform the Western genre to fit her specific story and form. She is able to capture the landscape in a way that is simultaneously vibrant and tranquil. She portrays this space as one that is home to many, departing from harmful representations of native people that steep the genre. They exist in this space, their home, and defend it from those that seek to harm it. When they see that Coyote isn't a threat, they welcome her to stay, healing her from wounds that were inflicted in self-defence. Their mode of living becomes an escape for the protagonist, a way to be part of a self-sustaining community that is in direct contrast with the harm that was caused in the community she was part of before. The native people are safety in a landscape that is filled with danger, departing from the Western demonisation of this group of people and opting for one that is more neutral, even positive.

This book creates its illustration through watercolour, or what looks like watercolour, giving the harsh desert a dream-like quality, further adding to the escapist fantasy that permeates the story. There are entire pages where it is just a drawing of the desert, often with Coyote in the mid-ground, dwarfed by her surroundings. These pages offer the reader moments of quiet amongst the danger, amongst the action, where you can sink into the sublime of the landscape. The silence within this book allows the reader to feel as small as Coyote does, to let the desert fully engulf you, to escape from your life and ride a horse through the various terrain.

|

| Source: Paris Review |

I've spoken about escapism a lot in this review. It is not my prerogative to be constantly talking about the pandemic on this blog. I feel like I've mentioned it in every post. But since we've gone back into another lockdown in the UK and I'm isolating alone, it's hard not to think of this book as an escape from the reality of the world.

There's a conversation about how healthy it is to use art as an escape. I'm not going to have it here. Here, I want to talk about the undeniable contrast between this dog lady being alone in the wilderness and those of us alone in our homes during this period. Unlike Coyote Doggirl, I cannot choose to abandon my life to exist in the wild. I must stay in place and help this country which cannot seem to get its shit together. This book offered a small respite, a pleasant and familiar kind of danger, where the harm being done felt material, and therefore, could actually be dealt with.

*

Thank you for reading this post! If you enjoyed it, please consider donating to my Ko-fi. It's a one time donation of £1 and it would really help me out x